PRiSM, the RNCM Centre for Practice & Research in Science & Music, is a collaborative, interdisciplinary research environment which sees composers and artists work with mathematicians and scientists to create new music. Now in its fifth year, PRiSM will mark its anniversary in tandem with the Royal Northern College of Music’s 50th birthday celebrations at the fourth annual Future Music festival.

The Future Music festival brings together creatives who are pioneering new developments at the intersection of music and technology. This year the festival consists of four events in Manchester, featuring a total of nine world premieres, including new works by composer and Director of PRiSM Emily Howard and Robert Laidlow, PRiSM’s Doctoral Researcher in Artificial Intelligence, a role held in association with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra.

PRS for Music classical relationship manager Daniel Lewis caught up with Emily and Robert ahead of the festival this week.

DL: Emily, can you introduce us to the work of PRiSM, which is now celebrating its fifth year?

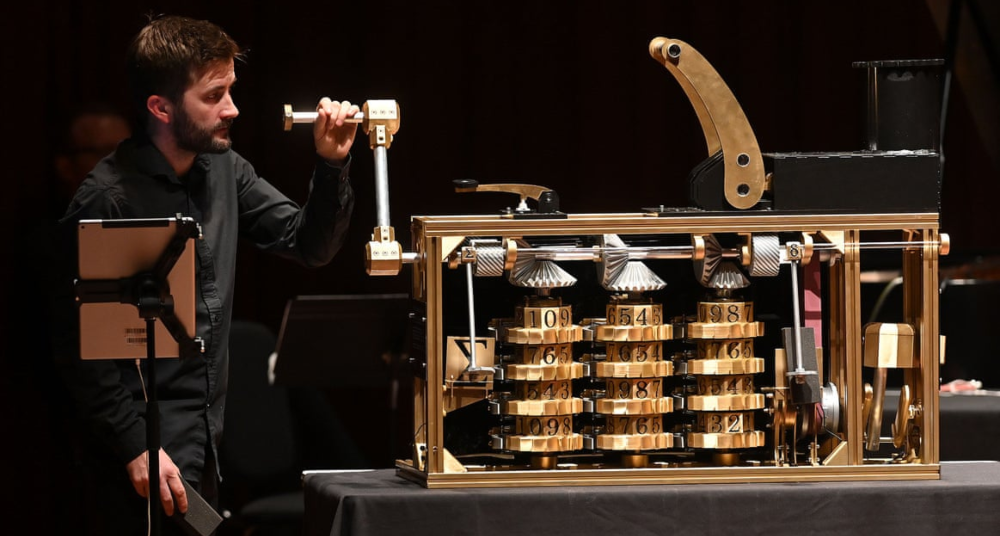

EH: PRiSM initially grew out of my interest in collaborating with mathematicians, and the influence of mathematics and science on my own work. During the Ada Lovelace bicentenary in 2015, I started working with mathematician Marcus du Sautoy, who is the Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Oxford. We worked on a gig together in 2017 for New Scientist Live called The Music of Proof. Through that project, we brought the idea of PRiSM to RNCM. We wanted an environment for artists, scientists, mathematicians and musicians to come together and chat. Since then, PRiSM has gone on to develop a speciality in AI and Music.

DL: From a composers’ perspective, what is the benefit of using mathematics or AI as inspiration for a piece?

EH: I’m very interested in getting away from what I would normally do. Composers often veer towards what they know, but I’m always trying to start from somewhere completely different. It’s a massive catalyst, and I love that.

DL: How would you explain the compositional process when working with mathematics or AI?

EH: A good way to explain is that we are asking questions. This could be ‘what happens if I’m thinking about travelling around this shape?’ or thinking about the idea of infinity within music.

RL: I like this idea of questions. My piece definitely asks ‘what is the role of AI in the creative process?’ And that opens the door to all sorts of questions about what creativity is. Is it an act that something does, or is creativity a trait that people have – and can computers have traits? I now think that creativity is more like a process.

There is also the idea of the orchestra, which is comprised of instruments that were invented hundreds of years ago – it’s like a museum of technologies. I’ve been trying to think about what that means today when we are so dependent on advanced technology. In what ways can the orchestra be relevant?

DL: How do you set about incorporating these new technologies in your music?

EH: One example is that PRiSM developed a computer-assisted compositional tool called PRiSM SampleRNN. If you put an audio dataset into SampleRNN, the software learns from it and produces something new from what it has learned. I wrote a string quartet (shield) where we recorded an hour of material which was then put through this algorithm. I used the output as inspiration for writing the piece.

RL: I also used SampleRNN for my piece Silicon, written for the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. We took a dataset of 2500 hours of the orchestras’ broadcasts on BBC Radio 3. This was used to train the SampleRNN, and it came out with shockingly good results.

DL: Rob, as an AI specialist, are there other ways you have incorporated AI in your music?

RL: In the second movement of Silicon, I incorporate a synthesizer that was developed with the Magenta lab at Google. The instrument uses DeepFake technology, which has been used in the film world to ‘bring back’ dead actors with AI. This is like the sonic version of that technology. This is interesting for a host of reasons. It uses new sounds within the orchestra, and also poses the question of what is real art, and what is not. Is DeepFake music the same as real music? Using this instrument in the context of an orchestra is interesting because orchestras think about authenticity in sophisticated ways, because of how many times the same pieces are performed differently.

DL: Both your pieces at Future Music festival are large-scale orchestral works. What do you like about working with orchestras?

RL: This is another question that I thought about with my piece. What is it about the orchestra that we enjoy? Is it the level of technical expertise? Or is it about playing this wonderful music that is amazingly well put together? We can feasibly think of an AI that might replicate a Beethoven symphony, but I still think people would go and see an orchestra perform the original. I think that’s something to do with the commonality of all these people in this ensemble, and that’s what people enjoy, the communal act.

EH: I completely agree. There’s a sheer pleasure in bringing together so many people and working with such a vast collective timbral palette. And I firmly believe that the shared connection that arises between so many players and an audience in live performance is infinitely meaningful.

DL: Rob, your piece was delayed due to the pandemic. How did that affect your composing?

RL: The piece was originally planned for May/June 2020, and it is now scheduled for October 2022. It was very beneficial for the piece, partially because the technology I wanted to use for the piece was invented between those times! I was sort of banking on the technology being finished, and it was only in December where I got my hands on what I wanted for the second movement.

Overall, the piece took around a year to write, and it was really wonderful to have the space to write something that felt finished because it is done, not because the deadline is fast approaching and you need to engrave the score, which is sometimes the case!

New works by Emily Howard and Robert Laidlow will be performed by the BBC Philharmonic on 29th October at Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, as part of the Future Music Festival. Tickets are available here.