Ever since Killzone exploded into life in November 2004, the video game series has evolved into an all-conquering blockbuster, spawning multiple sequels and garnering huge acclaim, sales and accolades. The second instalment of the series, Killzone 2, even generated a bit of history for its composer, Joris de Man, as its score went on to win the inaugural Ivor Novello Award for Best Original Video Game Score in May 2010.

‘Winning an Ivor was incredible. It was recognition for the whole of the video games music industry,’ Joris tells M 15 years on. ‘I’d always struggled a bit with imposter syndrome as a video game composer. When I started no one would take it seriously, and it certainly wasn’t seen as a career.’

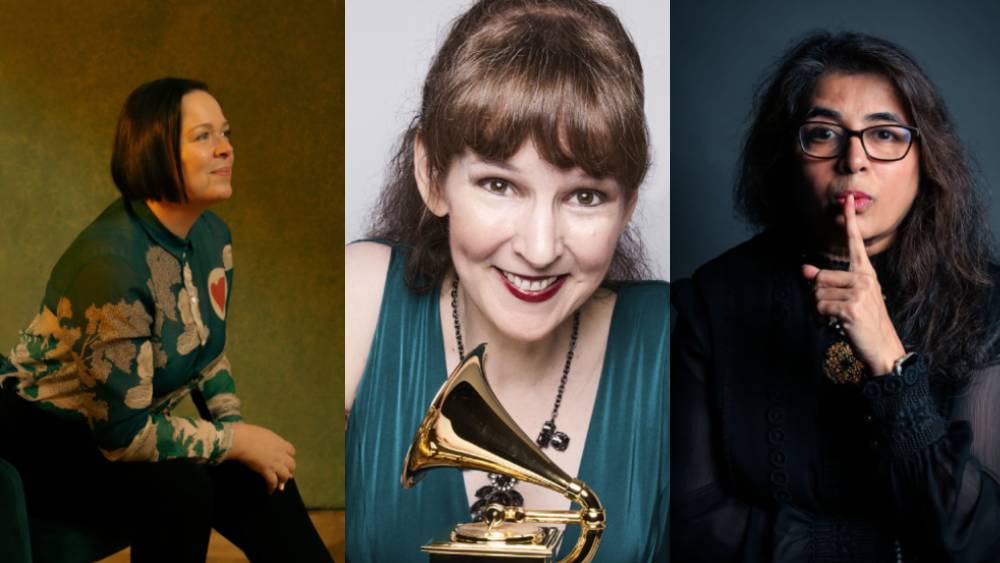

It’s thanks to the hard work of Joris and his peers like Jessica Curry, Richard Jacques and Lorne Balfe that the magic of video game soundtracks has soared over the last 15 years. These scores can now fill concert halls — BBC Proms dedicated an entire concert to gaming music at the Royal Albert Hall in 2022 — while Joris went on to secure a second Ivor Novello Award in 2018 for his work on Horizon Zero Dawn.

‘Being recognised by the Ivors certainly showed that people are taking [video game composition] seriously and recognising the effort that goes into it,’ the Dutch composer adds. ‘Composers are trying to write music that not only enhances a game but can also work outside of this setting. But never in a million years did I expect to win that first Ivor in 2010 — I was in utter disbelief.’

'Winning an Ivor was incredible. It was recognition for the whole of the video games music industry.’

Raised in a musical family in the Netherlands, Joris’ parents were classically trained musicians. ‘There were lots of weekends spent lugging my mother’s harpsichord into the back of a car and then heading off to a venue for a performance,’ he recalls. ‘A lot of my youth was spent in the back of the car, and I used to fall asleep on top of the instrument.’

Away from the car, Joris developed an early fascination with computers, particularly the Atari ST: ‘Many people know the Atari for its built-in MIDI ports and how it transformed making music, leading to the bedroom producer. I was making music with a sound chip — I spent one summer programming my own chip tracker. I became quite well known on the Atari scene, but it made me think I could start making music for games.’

Joris later became aware of the London-based game developer The Bitmap Brothers, who were behind such popular series as Speedball and Xenon. Having successfully thrusted a demo tape at the Brothers’ Eric Matthews during an event, Joris was later offered a job with the company.

‘That was the start. I thought amazing things were going to happen when I moved to London,’ he says. ‘But I worked for them for a year before they went bankrupt. I didn’t realise when I started with them that they were on the brink.’

After returning to the Netherlands Joris secured a role with Lost Boys Games, out of which Guerrilla Games (the developer behind Killzone and Horizon) emerged. ‘In those early days of the internet, it was like the one-eyed king in the land of the blind,’ Joris says with a laugh. ‘I was there from the start working on different titles, including what would go on to become the first ever Killzone.’

Joris was responsible for helming the orchestral score and sound design of Killzone. While the score for the first game was recorded in Prague due to budgetary constraints, the decision was made for its 2009 sequel to head to Abbey Road Studios to work with The Nimrod Session Orchestra — whose members included musicians who’d previously performed with the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

‘I like to write intensive music to [picture] that really gets involved in what’s going on on the screen,’ Joris explains about his process. ‘For Killzone 2, it worked out to be more affordable for us to record at Abbey Road. I'd never imagined I'd be recording in those hallowed halls!'

A few weeks before recording begun, he slipped and broke his ankle. ‘Usually, a game is divided between the in-game music, which is happening as you play, and the cinematics that tell the story and explain to the player why you’re behaving like you do,’ Joris explains. ‘As a composer, you usually have to write music for all these last-minute edits to the animation. As my foot was in a cast, I composed the whole live orchestral score with my leg up and my back in agony. I would compose for about eight hours, sleep for three hours, then go back to composing for another six-to-eight hours — with a constant drip-feed of Red Bull to keep me going.’

With the score only being finished 36 hours before the recording session began — copyists were still writing out the final parts as the orchestra arrived — Joris was relieved to be working with an ensemble of extremely competent musicians.

‘We had Maurice Murphy, the famous trumpeter who had played on the Raiders of the Lost Ark score, among some of London’s finest musicians. It was such a rush,’ Joris recalls. ‘They’d do a take and I’d just be gobsmacked at how good it had been, just an incredible level of musicianship. After the session, the players said how much they enjoyed playing it as they got to go full tilt. Some of [the score] is a bit over the top, but the idea was always for it to be like a space opera.’

'The idea for the Killzone 2 score was always for it to be like a space opera.'

Whichever visual medium Joris writes for, his process typically starts with him sitting at a piano sketching out ideas while using Nuendo, a digital audio workstation designed by Cubase developers Steinberg: ‘I start with the piano and just try to work out the bass, melody and chords. I’m not a great player, but I can massage things enough to get a sense of where they need to be and need to go in terms of arrangement.’

Joris cites John Williams, minimalist composer John Adams and Hans Zimmer among his chief influences. ‘Hans is one of the first composers who understood that it’s not just about recording an orchestra, but how you produce it too,’ Joris reasons. ‘I’d only made the link a while ago that Hans Zimmer used to be in a band with Trevor Horn. He’d taken Trevor Horn’s production style and applied it to film music — that’s the magic.’

Asked for his top tips for budding video game composers, Joris says that in-person connections and networking remain essential for those music creators looking to establish themselves in this increasingly competitive field.

‘It can come down to who you know and get along with,’ he adds. ‘A good starting point is to go to all the developer events, which happen around the world all the time, and go and make friends with people and make connections. You might find an indie developer who is working on a project that could lead to them becoming the triple AAA developer of tomorrow.’

Joris is living proof that working with a fledgling games developer from the onset can lead to bigger opportunities in the long run. It also means that both the developer and the composer can build their careers together. ‘That’s what happened with me and Guerilla Games,’ Joris explains. ‘I joined them when they were making Game Boy titles and had just the one PlayStation title. A few years later, they had a great Sony deal — things can happen quickly.’

He also points to the benefits of living ‘in this golden age of information’: ‘There’s so much you can learn online via YouTube tutorials and tools like Unity that are free to use. It’s a fantastic time to be entering the world of music composition — there’s more competition, but also more opportunities.

‘We’re seeing the gaming world continue to change, in part due to the success of things like The Last of Us and the Fallout series and the proliferation of live concerts. It means there’s a whole new generation experiencing this music in new and exciting settings. It’s amazing to see.’