Anita Awbi chats to the circuit benders and aural evangelists who are stepping out from behind their laptops to make the most of the new hardware boom.

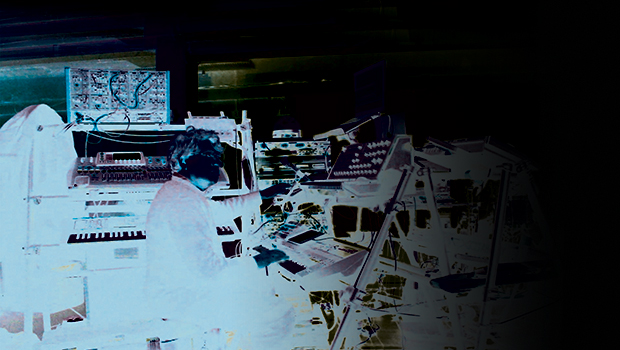

In 1978, a little known Sheffield musician called Martyn Ware fired up his Korg 700S analogue synthesiser and began creating the shifting industrial basslines and melodic wobble that would soon become the Human League’s first single Being Boiled.

It took less than three quid to make, using only a reel-to-reel tape recorder, microphone and two synths (the other being a Roland System 100). Martyn had no mixing desk, no equalisers or compressors, no effects and definitely no midi. Yet the finished article went on to define an important era in British electronic pop.

‘It was all played manually’, Martyn remembers, ‘I know it’s hard to imagine a time before midi - it’s a bit like Jurassic Park – but without it you couldn’t synchronise anything. You’d get a hardware sequencer, create the beats from scratch – a kick drum, a snare, a hi-hat – and then play stuff over the top by bouncing from track to track on the reel-to-reel recorder. That’s as basic as you can get, it’s almost hobbyist level,’ he explains.

Among all the drones and dissonance, a new way of making music had emerged that was as unique as the equipment it was created on. And, despite all the amazing tech advances we’ve since enjoyed, it’s a method that artists and songwriters are increasingly revisiting.

Throwing shapes

On first listen, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, Kraftwerk’s Autobahn and Sun Ra’s The Wind Speaks have very little in common. But on closer inspection, a familiar, bassy resonance emerges – the unmistakable burble of Bob Moog’s revered MiniMoog monophonic synthesiser.

The hardy bit of kit, created in 1969, went on to shape a decade of iconic cuts from Parliament to Emerson, Lake and Palmer and many more. It was the first time an analogue synth really left its mark on modern music. It sparked a revolution in experimentalism which touched all genres and created a groundswell of exciting and original thought.

Fast forward to 2015 and it seems that everyone from Coldplay to Trent Reznor, Bastille to Lorde, are experimenting with electronic hardware and overdosing on oscillators. This surge in popularity for the classic synth sound, coupled with a desire to experience tactile hardware, is now tempting a wave of artists away from their PCs to seek out the real thing. Time will tell if this trend sparks a lasting creativity that can redefine the parameters of music-making again.

In 1978, a little known Sheffield musician called Martyn Ware fired up his Korg 700S analogue synthesiser and began creating the shifting industrial basslines and melodic wobble that would soon become the Human League’s first single Being Boiled.

It took less than three quid to make, using only a reel-to-reel tape recorder, microphone and two synths (the other being a Roland System 100). Martyn had no mixing desk, no equalisers or compressors, no effects and definitely no midi. Yet the finished article went on to define an important era in British electronic pop.

‘It was all played manually’, Martyn remembers, ‘I know it’s hard to imagine a time before midi - it’s a bit like Jurassic Park – but without it you couldn’t synchronise anything. You’d get a hardware sequencer, create the beats from scratch – a kick drum, a snare, a hi-hat – and then play stuff over the top by bouncing from track to track on the reel-to-reel recorder. That’s as basic as you can get, it’s almost hobbyist level,’ he explains.

Among all the drones and dissonance, a new way of making music had emerged that was as unique as the equipment it was created on. And, despite all the amazing tech advances we’ve since enjoyed, it’s a method that artists and songwriters are increasingly revisiting.

Throwing shapes

On first listen, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, Kraftwerk’s Autobahn and Sun Ra’s The Wind Speaks have very little in common. But on closer inspection, a familiar, bassy resonance emerges – the unmistakable burble of Bob Moog’s revered MiniMoog monophonic synthesiser.

The hardy bit of kit, created in 1969, went on to shape a decade of iconic cuts from Parliament to Emerson, Lake and Palmer and many more. It was the first time an analogue synth really left its mark on modern music. It sparked a revolution in experimentalism which touched all genres and created a groundswell of exciting and original thought.

Fast forward to 2015 and it seems that everyone from Coldplay to Trent Reznor, Bastille to Lorde, are experimenting with electronic hardware and overdosing on oscillators. This surge in popularity for the classic synth sound, coupled with a desire to experience tactile hardware, is now tempting a wave of artists away from their PCs to seek out the real thing. Time will tell if this trend sparks a lasting creativity that can redefine the parameters of music-making again.

Synths sell

These days, historic brands like Moog, Roland and Korg are operating in a market buzzing with boutique circuit benders and iconic hardware reissues. Some are ‘plug-in’ products which pay homage to the original masters (‘soft’ synths providing simulated sounds within the PC), but the biggest growth is in new hardware which contains hybridised analogue/digital technology that’s fit for the 21st century.

Testament to their mounting success, international trade show NAMM attracted a record 130 hardware brands to exhibit at its US event in January – up 20 percent on the previous year. And, as many household names develop cheaper, more accessible analogue (and analogue-inspired) synths, drum machines and effects units - some which retail for under £30 – the trend is only set to grow.

The healthy hardware market, having recently suffered several years of flat sales, is now crystallised by boutique companies like Jack White’s Third Man Records, which recently teamed up with boutique synth manufacturer Critter and Guitari on a range of quirky, customisable gear.

Elsewhere, electronic legend and modular synth guru Vince Clarke has joined forces with Analogue Solution to launch a new Clarke Circuits range. But this isn’t all about niche product - NAMM figures show that, since 2009, retail sales of keyboard synthesisers have increased across the board by 15.9 percent, and are up more than 32 percent over the last decade.

Korg’s Sale and Marketing Director Richard Hodgson explains: ‘We’re seeing a growing trend in people of all ages interested in hardware and analogue purity, and who are creating individual music. Now that analogue synthesisers are becoming cheaper and more accessible, it’s breeding a new type of musician who wants to experiment. It’s a really exciting time.

These days, historic brands like Moog, Roland and Korg are operating in a market buzzing with boutique circuit benders and iconic hardware reissues. Some are ‘plug-in’ products which pay homage to the original masters (‘soft’ synths providing simulated sounds within the PC), but the biggest growth is in new hardware which contains hybridised analogue/digital technology that’s fit for the 21st century.

Testament to their mounting success, international trade show NAMM attracted a record 130 hardware brands to exhibit at its US event in January – up 20 percent on the previous year. And, as many household names develop cheaper, more accessible analogue (and analogue-inspired) synths, drum machines and effects units - some which retail for under £30 – the trend is only set to grow.

The healthy hardware market, having recently suffered several years of flat sales, is now crystallised by boutique companies like Jack White’s Third Man Records, which recently teamed up with boutique synth manufacturer Critter and Guitari on a range of quirky, customisable gear.

Elsewhere, electronic legend and modular synth guru Vince Clarke has joined forces with Analogue Solution to launch a new Clarke Circuits range. But this isn’t all about niche product - NAMM figures show that, since 2009, retail sales of keyboard synthesisers have increased across the board by 15.9 percent, and are up more than 32 percent over the last decade.

Korg’s Sale and Marketing Director Richard Hodgson explains: ‘We’re seeing a growing trend in people of all ages interested in hardware and analogue purity, and who are creating individual music. Now that analogue synthesisers are becoming cheaper and more accessible, it’s breeding a new type of musician who wants to experiment. It’s a really exciting time.

Live modulation

It’s fair to say that the continued popularity of electronic dance music (EDM), underground techno and scuzzy indie-rock has enticed more musicians and producers from other genres to dive into the wonky world of analogue synths and create unique studio sounds. But the trend is also changing the face of live performance, with many dance music producers coming out from behind their laptops to helm improvised shows based around hardware kit and analogue discordance.

Stephen Bishop, founder of the Middlesbrough-born Opal Tapes label home to analogue purists such as Karen Gwyer and Patricia (recently seen demoing new modular products for Moog), believes that such kit often lends itself more easily to unrestrained live gigs. ‘Analogue equipment requires practice and learning to use properly,’ he says. ‘This in itself creates a work flow which transfers into live practice and often into recording style. Layers accrue and build. The individual parts sum into the song as a whole. Addition and subtraction are still key when using analogue equipment – as is a constant ear given to the mix - as the interaction of voltage is different to that of digital code.’

Stephen writes and records as Basic House and, over the last few years, has collected a motley crew of likeminded artists from around the globe who fit his rare taste for fugitive house and broken-down techno. As the name suggests, Opal Tapes’ musical output is mainly cassette and vinyl, in keeping with Stephen’s passion for real analogue sound.

It’s fair to say that the continued popularity of electronic dance music (EDM), underground techno and scuzzy indie-rock has enticed more musicians and producers from other genres to dive into the wonky world of analogue synths and create unique studio sounds. But the trend is also changing the face of live performance, with many dance music producers coming out from behind their laptops to helm improvised shows based around hardware kit and analogue discordance.

Stephen Bishop, founder of the Middlesbrough-born Opal Tapes label home to analogue purists such as Karen Gwyer and Patricia (recently seen demoing new modular products for Moog), believes that such kit often lends itself more easily to unrestrained live gigs. ‘Analogue equipment requires practice and learning to use properly,’ he says. ‘This in itself creates a work flow which transfers into live practice and often into recording style. Layers accrue and build. The individual parts sum into the song as a whole. Addition and subtraction are still key when using analogue equipment – as is a constant ear given to the mix - as the interaction of voltage is different to that of digital code.’

Stephen writes and records as Basic House and, over the last few years, has collected a motley crew of likeminded artists from around the globe who fit his rare taste for fugitive house and broken-down techno. As the name suggests, Opal Tapes’ musical output is mainly cassette and vinyl, in keeping with Stephen’s passion for real analogue sound.

Hardware hype

But is this all hype? What is it about analogue instruments, hardware synths and recording techniques that are so appealing? Award-winning producer and engineer Richard Formby has some ideas. Throughout a 25 year career, which started with a bang when he produced the mind-expanding synth and guitar musings of Spacemen 3, Richard has learned the old fashioned basics, kept abreast of the digital revolution and maintained a handy side line in real analogue production. He now uses a combination of tools, including in-the-box PC package Logic and old school analogue gear - the results of which are best heard on recent albums by Mercury Prize-tipped Ghostpoet and Ivor Novello Award-nominated Wild Beasts. Despite his digital multitasking, Richard still understands the true appeal of analogue.

He believes that the warm, physical characteristics of recordings are disappearing as digital perfectionism replaces analogue anomalies and human performance error. ‘When you correct something on Pro Tools or Logic, each little digital correction is a little bit of character removed from the original person’s performance. The more of those you do, the more character you’re taking out of it until you end up with something which is quite bland.’

But is this all hype? What is it about analogue instruments, hardware synths and recording techniques that are so appealing? Award-winning producer and engineer Richard Formby has some ideas. Throughout a 25 year career, which started with a bang when he produced the mind-expanding synth and guitar musings of Spacemen 3, Richard has learned the old fashioned basics, kept abreast of the digital revolution and maintained a handy side line in real analogue production. He now uses a combination of tools, including in-the-box PC package Logic and old school analogue gear - the results of which are best heard on recent albums by Mercury Prize-tipped Ghostpoet and Ivor Novello Award-nominated Wild Beasts. Despite his digital multitasking, Richard still understands the true appeal of analogue.

He believes that the warm, physical characteristics of recordings are disappearing as digital perfectionism replaces analogue anomalies and human performance error. ‘When you correct something on Pro Tools or Logic, each little digital correction is a little bit of character removed from the original person’s performance. The more of those you do, the more character you’re taking out of it until you end up with something which is quite bland.’

Credible shortcuts

As more artists and songwriters venture out the box to explore hardware instruments, many are increasingly drawn to analogue equipment too. They are discovering a tactile approach to music-making and sound manipulation, and are rediscovering the art of live recording. So much so that analogue has become a buzzword for just about anyone who has a passion for ‘authentic’ music. Wrapped up in all of this is vinyl sales, which have seen a massive resurgence the past two years. Elsewhere, everyone from The Barbican (Moog Concordance, 8 July) to Brighton Music Conference are hosting days devoted to analogue performance, recordings and hardware.

But Luke Abbott, a Norfolk based electronic producer who has released music both on his own label and James Holden’s Border Community imprint, has been exploring the furrows of experimental modulation since 2006. He seems much more pragmatic about the umbrella term.

‘There’s a lot of focus on the word “analogue”,’ he says, ‘which for a lot of people seems to equate directly to the idea of credibility - but it really doesn’t. The fact is, there’s a lot of music equipment out there that does very specific jobs, and I’ve got very specific ideas about how I want things to work, so I end up using what I need to do what I want.’

Right now, Luke is most interested in hybridisation, which allows contrasting music technologies to work together. ‘Music composition is a very broad term that encompasses a vast number of approaches that are constantly expanding and developing into new techniques with new applications,’ he explains. ‘It’s like a Deleuzian rhizome or something. Modular synthesis is caught up in that flow right now, and it’s pretty exciting to see how wildly that world is developing with so many small companies making such a diverse range of new tools.’

Mark Ayres, from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, agrees: ‘The whole ethos of what we’re doing is predicated on the history of technology. There’s such a huge range of tools available to us now. We use two Mac computers, soft synths and sequencers – but we also have a stage full of old analogue boxes.’

And, for electronic luminaries such as Martyn Ware, it’s the hybridisation and analogue-simulation in digital technologies that are most exciting. Having grown up in an era of open circuitry and electronic wizardry, he carries a deep appreciation for analogue music and hardware equipment.

‘I think we have lost the patina of age in digital music, because it’s infinitely replicable and doesn’t age,’ he says. ‘And we’re living in a world where there’s massive ease of use. You can create and mix a track from scratch in a couple of hours and it will sound pretty good. But it won’t have that magic 10 percent on the top end because it’s been too easy – and that’s the issue with in-the-box digital. It’s a bit too easy, and it’s a bit too fast, to do the same tricks over and over again. In fact, I spend half my time trying to stop things sounding so digital!’

This feature was first published in the latest edition of M magazine - read the full print edition online here:

http://www.m-magazine.co.uk/features/archive/in-print-m56/

As more artists and songwriters venture out the box to explore hardware instruments, many are increasingly drawn to analogue equipment too. They are discovering a tactile approach to music-making and sound manipulation, and are rediscovering the art of live recording. So much so that analogue has become a buzzword for just about anyone who has a passion for ‘authentic’ music. Wrapped up in all of this is vinyl sales, which have seen a massive resurgence the past two years. Elsewhere, everyone from The Barbican (Moog Concordance, 8 July) to Brighton Music Conference are hosting days devoted to analogue performance, recordings and hardware.

But Luke Abbott, a Norfolk based electronic producer who has released music both on his own label and James Holden’s Border Community imprint, has been exploring the furrows of experimental modulation since 2006. He seems much more pragmatic about the umbrella term.

‘There’s a lot of focus on the word “analogue”,’ he says, ‘which for a lot of people seems to equate directly to the idea of credibility - but it really doesn’t. The fact is, there’s a lot of music equipment out there that does very specific jobs, and I’ve got very specific ideas about how I want things to work, so I end up using what I need to do what I want.’

Right now, Luke is most interested in hybridisation, which allows contrasting music technologies to work together. ‘Music composition is a very broad term that encompasses a vast number of approaches that are constantly expanding and developing into new techniques with new applications,’ he explains. ‘It’s like a Deleuzian rhizome or something. Modular synthesis is caught up in that flow right now, and it’s pretty exciting to see how wildly that world is developing with so many small companies making such a diverse range of new tools.’

Mark Ayres, from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, agrees: ‘The whole ethos of what we’re doing is predicated on the history of technology. There’s such a huge range of tools available to us now. We use two Mac computers, soft synths and sequencers – but we also have a stage full of old analogue boxes.’

And, for electronic luminaries such as Martyn Ware, it’s the hybridisation and analogue-simulation in digital technologies that are most exciting. Having grown up in an era of open circuitry and electronic wizardry, he carries a deep appreciation for analogue music and hardware equipment.

‘I think we have lost the patina of age in digital music, because it’s infinitely replicable and doesn’t age,’ he says. ‘And we’re living in a world where there’s massive ease of use. You can create and mix a track from scratch in a couple of hours and it will sound pretty good. But it won’t have that magic 10 percent on the top end because it’s been too easy – and that’s the issue with in-the-box digital. It’s a bit too easy, and it’s a bit too fast, to do the same tricks over and over again. In fact, I spend half my time trying to stop things sounding so digital!’

This feature was first published in the latest edition of M magazine - read the full print edition online here:

http://www.m-magazine.co.uk/features/archive/in-print-m56/

.ashx?h=67&w=80&la=en&hash=340524FD746527338490DF251ABF8B71)