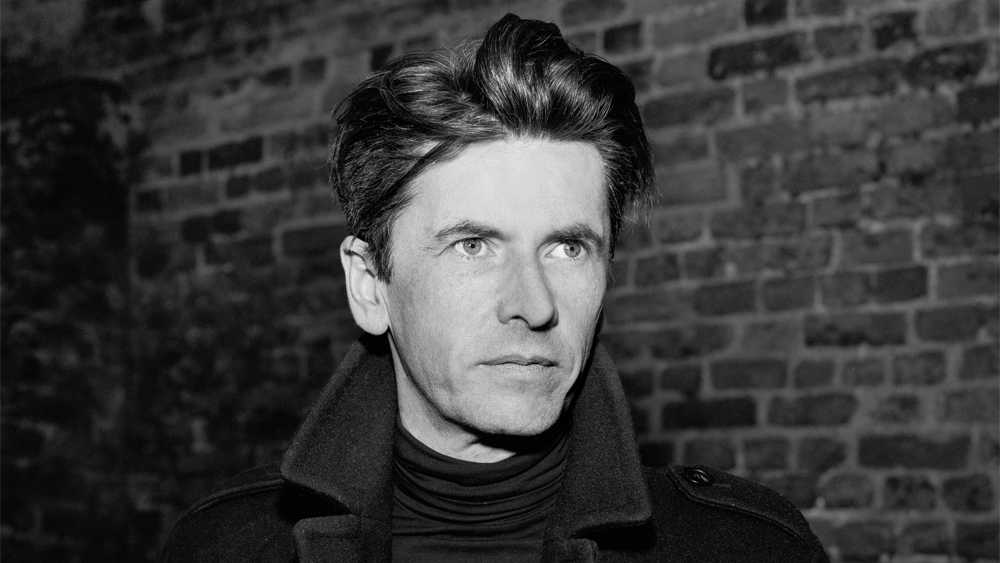

Since the early nineties Bernard has thrived on interacting with a rolling cast of collaborators.

Rather than settle for the early success he found with Suede, Bernard left the band at the height of their success to pursue new collaborations and solo work.

Following his partnership with David McAlmont, a record with Suede’s Brett Anderson as The Tears and a couple of solo records, he began to branch out into producing and writing for other artists.

Since contributing to Welsh singer Duffy’s multi-million selling debut Rockaferry, Bernard has gone on to produce records for acts like The Libertines, Kate Nash, Tricky and Paloma Faith.

Later this month, he is set to impart his substantial knowledge and experience at Tipping Point Live in Newcastle for a special live songwriting masterclass.

Here, we catch up with Bernard to get his take on what makes a great song, how he writes and his advice for emerging songwriters…

How did you first get involved with Tipping Point Live?

One of the organisers I’d worked with before, from a band called Frankie & the Heartstrings. Because I’d spent some time in Newcastle and Sunderland with those guys a few years ago, I just loved being in the north east, so he just suggested it. When he suggested doing something I had a good idea about something particular I could do rather than just doing a show or something.

And you came up with a masterclass.

I hate the term masterclass to be honest. It sounds a bit wanky and puts me on a pedestal a little bit. But what I do is kind of the opposite of a masterclass, because the whole point of it is inclusion and for me to be part of the group. And to show people what we can do together.

I’m not there to write people’s songs and for me to do that – going back to the idea of a masterclass – is like saying, “stand back, I’m a real musician,” which is not what I like to do.

What challenges do you anticipate the live aspect of the masterclass will throw up?

People getting very bored [laughs]. I’ve done it once before with an audience at a college and it was brilliant actually. My experience of doing this – I tutor two days a week in London and I do eight of these sessions a week, so I’ve done over 400 songs in this way and with young people – is that the room is overwhelmingly positive and supportive and that’s a really interesting thing. From the background that I come from in music, things were very bitchy and competitive from a sense that people wanted to put you down and put you in your place and knock you down and knock you back, that’s certainly my first experience of music.

That wasn’t very supportive, and in this situation what I find really gratifying is that if you put young people in these situations, they’re not over competitive and they’re supportive of each other.

The only ego in the room is the song itself. That’s a tricky thing to overcome, because your song, your work, is your baby. It’s precious, you want to protect it. The more you protect something, the less you can set it free. The more you hold on to something the less you see the possibilities of what could happen.

Personality, that’s all. Because everything is possible and everything can be achieved quite quickly on a laptop or on a phone or something, it almost makes it a bit dull. Software is a bit dull, it’s fantastic, we achieve amazing things through it, and we all use it. I use it. But trying to be impressed by the software itself? Those days have gone.

It strikes me, the more and more into that world we go, the more I reach out for or look for is the only thing that’s unique in a human being, and that’s DNA, personality. What’s unique about you? What’s beautiful about your experience. What are your weaknesses? What are your strengths? Look at those things when you go to write a song, what’s interesting about you.

What for you makes a great song?

Something that you go away from and you feel that it means something to you. It affects your life, it affects your feelings, it makes you feel great, it makes you feel sad, it makes you cry, it makes you laugh. It makes you want to put it on when you’re a million miles away from where you first heard it, and you’re a million miles away from the person who wrote it. It adds something to your life, it adds a perspective to your life, or your vision of life. That’s what all great art is.

Do you follow a specific process when songwriting?

It depends whether I’m writing on my own or with somebody else. If it’s with somebody else, I’m waiting for that person, I’m waiting for what I can get out of that person and for them to feed into the situation. Quite often it’s about saying the things you’re pissed off about and crystalizing it into a very memorable line. Things that feel musical and sound musical. I don’t look at it in a particular format.

What is it that drives you to writing for and with other people?

I like collaborating with people, I think there’s a real joy in it. I like being around musicians, I like hearing about them. I’m curious about music and I like absorbing what other people have learnt and where they’ve come from. I’ve always loved that, which is why I’ve not been in a group for a hundred years because I really enjoy thinking, “what are we going today? Who are you?”

Young musicians spend an awful lot of time on their own, on laptops, I bedrooms with headphones. They’re creating on their own in quite an isolated sense. Where I came from the only way to make music was to get into a room with people and make noise. That was very easy to do, it’s much more difficult to do that these days.

This is one of the big things that I want to demonstrate, is how quickly we can produce a song when you’ve got bodies in a room. When there’re loads of people in the room, there’s always going to be somebody that can play another guitar, play a tambourine and that can come together very quickly. They’re part of a creative process. That eggs you on and gives you confidence.

That feeds into the argument about how we use social media and how that affects young people. They’re very introverted and go into a shell. They’re always looking at people doing incredible things all over the world and so you’re fantasising all the time and feel crushed by the possibility of not being able to do it. But if you step outside and go into a room with real human beings, here’s all the things that can happen.

In the real world it’s definitely quite difficult because we have venues closing everywhere, rehearsal rooms are quite hard to find – and can be quite expensive and prohibitive. Basically, it’s more convenient to hole-up in your room. There’s a huge side of that that’s brilliant as well. Being isolated and doing something in a very lonely way, I don’t knock that at all. But I’m just trying to encourage what could happen if you cross that bridge and interact with people.

What advice would you give to emerging songwriters?

Just be with other people, find other people, work with as many people as possible. Every time you work with somebody, play your song to somebody, chat with them, jam with them, you learn from them. You’re learning all the time an you’re learning about other people’s music. You’re learning techniques and processes and you take those back and you use them with what you do.

That’s the huge lesson that I’ve learned is to be a part of something, don’t try and be the boss. You don’t have to be the singer, the guitar player, the person who does it. Just be in the room and then when you get that moment to do that thing on your own, you’ll bring all these things and they’ll all feed into what you do. I do these sessions and I learn – the students don’t believe that – but I do it then I go away and nick all their ideas [laughs].

How do you balance it all? Does one have prominence over the others?

It’s whatever I’m doing today. I think it balances itself. Occasionally, I think to myself, "I haven’t done that in a while.” My teaching role ends this week until October again. Last week I was at the Barbican to celebrate Tropic Records, it famously has a huge folk catalogue. Today I’m doing some producing, an artist called Roxanne de Bastion. It’s quite electronic. Then next week I’m starting a record with Mark Eitzel, who’s coming over from America, and that’s going to be piano and guitar and stuff. I am all over the place, all of the time.

I work. I tell my students, “what you do today is great, but it’s what you do next week.” You never stop looking for work. There’s no company car as a musician, you’re always looking for a job and that means you’re always looking for opportunities. That’s why working with as many people as possible is so important. You do one thing and you’re always looking over your shoulder for what happens next. I’m very lucky that I’ve had some amazing opportunities in my career.

My students are in the same queue as me, we’re all in the same queue looking to do something. It’s an exciting way to live life.

Tipping Point Live takes place from 21 to 22 June. For more information, please visit generator.org.uk

bernardbutler.com